- Home

- Alice Walker

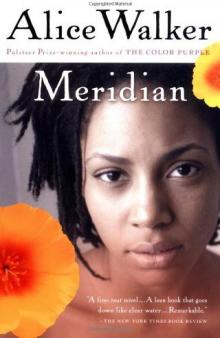

Meridian (1976) Page 5

Meridian (1976) Read online

Page 5

“Move that thing,” her mother said sharply. “Don’t you see I’m trying to get these peas ready for supper?”

“But it’s gold!” she insisted. “Feel how heavy it is. Look how yellow it is. It’s gold, and it could make us rich!”

But her mother was not impressed. Neither was her father or her brothers. She took her bar of gold and filed all the rust off it until it shone like a huge tooth. She put it in a shoe box and buried it under the magnolia tree that grew in the yard. About once a week she dug it up to look at it. Then she dug it up less and less ... until finally she forgot to dig it up. Her mind turned to other things.

Indians and Ecstasy

MERIDIAN’S FATHER HAD BUILT for himself a small white room like a tool shed in the back yard, with two small windows, like the eyes of an owl, high up under the roof. One summer when the weather was very hot, she noticed the door open and had tiptoed inside. Her father sat at a tiny brown table poring over a map. It was an old map, yellowed and cracked with frayed edges, that showed the ancient settlements of Indians in North America. Meridian stared around the room in wonder. All over the walls were photographs of Indians: Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Geronimo, Little Bear, Yellow Flower, and even a drawing of Minnehaha and Hiawatha. There were actual photographs, perhaps priceless ones—which apparently her father had spent years collecting—of Indian women and children looking starved and glassy-eyed and doomed into the camera. There were also books on Indians, on their land rights, reservations, and their wars. As she tiptoed closer to the bookshelves and reached to touch a photograph of a frozen Indian child (whose mother lay beside her in a bloody heap) her father looked up from his map, his face wet with tears, which she mistook, for a moment, for sweat. Shocked and frightened, she ran away.

One day she overheard her parents talking. Her mother was filling fruit jars in the kitchen: “So you’ve gone and done it, have you?” said her mother, pouring apple slices into the jars with a sloshing noise.

“But the land already belonged to them,” her father said, “I was just holding it. The rows of my cabbages and tomatoes run right up along the biggest coil of the Sacred Serpent. That mound is full of dead Indians. Our food is made healthy from the iron and calcium from their bones. Course, since it’s a cemetery, we shouldn’t own it anyhow.”

Before the new road was cut it had not been possible to see the Serpent from the old one. It was news to most of the townspeople that an Indian mound existed there.

“That’s disgusting,” said her mother. “How can I enjoy my food if you’re going to talk about dead Indians?”

“The mound is thousands of years old,” said her father. “There’s nothing but dust and minerals in there now.”

“But to give our land to a naked Indian—”

“Naked? He ain’t naked. You believe all that stuff they put on television. He wears a workshirt and blue jeans. His hair is the only thing that looks like Indians look on TV. It’s cut off short though, blunt, right behind the jowls, like Johnny Cash’s.”

“How do you know he ain’t a white man playing Indian?”

“Because I know. Grown-up white men don’t want to pretend to be anything else. Not even for a minute.”

“They’ll become anything for as long as it takes to steal some land.”

And once Meridian had actually seen the Indian. A tall, heavy man in cowboy boots, had his face full of creases like a brown paper bag someone had oiled and pinched a lot of lines in with careless fingers. Squinty black eyes stared with steady intensity into space. He was a wanderer, a mourner, like her father; she could begin to recognize what her father was by looking at him. Only he wandered physically, with his body, not walking across maps with his fingers as her father did. And he mourned dry-eyed. She could not imagine that weathered dusky skin bathed in tears. She could not see his stout dirt-ringed wrists pressing against his silver temples, or flattening in despair the remainder of his still-black hair.

His name was Walter Longknife. Which caused Meridian to swallow her first hello when they were introduced, and he came from Oklahoma. He had started out in an old pickup truck that broke down in the shadow of Stone Mountain. He abandoned it, and was glad, he said—in a slurred voice, as if he were drunk, which he was not—to walk through the land of his ancestors, the Cherokees.

Her father gave Mr. Longknife the deed to the sixty acres his grandfather acquired after the Civil War. Land too rocky for plowing (until her father and brothers removed all the rocks by hand and wheelbarrow), and too hilly to be easy to sell (prospective buyers always thought the mounds were peculiar hills). Mr. Longknife had kept the paper in his shirt until he was ready to move on—he spent most of the summer camping out on the land—and then he had given it back to her father.

“Other men run away from their families outright,” said her mother. “You stay, but give the land under our feet away. I guess that makes you a hero.”

“We were part of it, you know,” her father said.

“Part of what?”

“Their disappearance.”

“Hah,” said her mother. “You might have been, but I wasn’t even born. Besides, you told me how surprised you were to find that some of them had the nerve to fight for the South in the Civil War. That ought to make up for those few black soldiers who rode against Indians in the Western cavalry.”

Her father sighed. “I never said either side was innocent or guilty, just ignorant. They’ve been a part of it, we’ve been a part of it, everybody’s been a part of it for a long time.”

“I know,” said her mother, scornfully, “and you would just fly away, if you could.”

Meridian’s father said that Mr. Longknife had killed a lot of people, mainly Italians, in the Second World War. The reasons he’d done this remained abstract. That was why he was a wanderer. He was looking for reasons, answers, anything to keep his historical vision of himself as a just person from falling apart.

“The answer to everything,” said Meridian’s mother, “is we live in America and we’re not rich.”

One day when she was helping her father tie up some running beans, three white men in government-issued trucks—army green with white lettering on the side—came out to the farm. They unloaded a large wire trash basket and two brown picnic tables. They said a bulldozer would be coming the next day. The Indian burial mounds of the Sacred Serpent and her father’s garden of prize beans, corn and squash were to be turned into a tourist attraction, a public park.

When her father went to the county courthouse with his deed, the officials said they could offer only token payment; that, and the warning to stay away from Sacred Serpent Park which, now that it belonged to the public, was of course not open to Colored.

Each afternoon after school her father had gone out to the farm. It was beautiful land made more impressive by the five-hundred-yard Sacred Serpent that formed a curving, twisting hill beyond the corn. The garden itself was in rich, flat land that fitted into the curves of the Sacred Serpent like the waves of the ocean fit the shore. Across from the Serpent and the garden was a slow-moving creek that was brown and sluggish and thick, like a stream of liquid snuff. Meridian had always enjoyed being on the farm with him, though they rarely talked. Her brothers were not interested in farming, had no feeling for the land or for Indians or for crops. They ate the fresh produce their father provided while talking of cars and engines and tires and cut-rate hubcaps. They considered working at gas stations a step up. Anything but being farmers. To them the word “farm” was actually used as a curse word.

“Aw, go on back to the farm,” they growled over delicious meals.

But Meridian grieved with her father about the loss of the farm, now Sacred Serpent Park. For she understood his gifts came too late and were refused, and his pleasures were stolen away.

Where the springing head of the Sacred Serpent crossed the barbed-wire fence of the adjoining farm, it had been flattened years before by a farmer who raised wheat. This was long before Me

ridian or her father was born. Her father’s grandmother, a woman it was said of some slight and harmless madness, and whose name was Feather Mae, had fought with her husband to save the snake. He had wanted to flatten his part of the burial mound as well and scatter the fragmented bones of the Indians to the winds. “It may not mean anything to you to plant food over other folks’ bones,” Feather Mae had told her husband, “but if you do you needn’t expect me to eat another mouthful in your house!”

It was whispered too that Feather Mae had been very hot, and so Meridian’s great-grandfather had not liked to offend her, since he could not bear to suffer the lonely consequences.

She had liked to go there, Feather Mae had, and sit on the Serpent’s back, her long legs dangling while she sucked on a weed stem. She was becoming a woman—this was before she married Meridian’s insatiable great-grandfather—and would soon be married, soon be expecting, soon be like her own mother, a strong silent woman who seemed always to be washing or ironing or cooking or rousing her family from naps to go back to work in the fields. Meridian’s great-grandmother dreamed, with the sun across her legs and her black, moon-bright face open to the view.

One day she watched some squirrels playing up and down the Serpent’s sides. When they disappeared she rose and followed them to the center of the Serpent’s coiled tail, a pit forty feet deep, with smooth green sides. When she stood in the center of the pit, with the sun blazing down directly over her, something extraordinary happened to her. She felt as if she had stepped into another world, into a different kind of air. The green walls began to spin, and her feeling rose to such a high pitch the next thing she knew she was getting up off the ground. She knew she had fainted but she felt neither weakened nor ill. She felt renewed, as from some strange spiritual intoxication. Her blood made warm explosions through her body, and her eyelids stung and tingled.

Later, Feather Mae renounced all religion that was not based on the experience of physical ecstasy—thereby shocking her Baptist church and its unsympathetic congregation—and near the end of her life she loved walking nude about her yard and worshiped only the sun.

This was the story that was passed down to Meridian.

It was to this spot, the pit, that Meridian went often. Seeking to understand her great-grandmother’s ecstasy and her father’s compassion for people dead centuries before he was born, she watched him enter the deep well of the Serpent’s coiled tail and return to his cornfield with his whole frame radiating brightness like the space around a flame. For Meridian, there was at first a sense of vast isolation. When she raised her eyes to the pit’s rim high above her head she saw the sky as completely round as the bottom of a bowl, and the clouds that drifted slowly over her were like a mass of smoke cupped in downward-slanting palms. She was a dot, a speck in creation, alone and hidden. She had contact with no other living thing; instead she was surrounded by the dead. At first this frightened her, being so utterly small, encircled by ancient silent walls filled with bones, alone in a place not meant for her. But she remembered Feather Mae and stood patiently, willing her fear away. And it had happened to her.

From a spot at the back of her left leg there began a stinging sensation, which, had she not been standing so purposely calm and waiting, she might have dismissed as a sign of anxiety or fatigue. Then her right palm, and her left, began to feel as if someone had slapped them. But it was in her head that the lightness started. It was as if the walls of earth that enclosed her rushed outward, leveling themselves at a dizzying rate, and then spinning wildly, lifting her out of her body and giving her the feeling of flying. And in this movement she saw the faces of her family, the branches of trees, the wings of birds, the corners of houses, blades of grass and petals of flowers rush toward a central point high above her and she was drawn with them, as whirling, as bright, as free, as they. Then the outward flow, the rush of images, returned to the center of the pit where she stood, and what had left her at its going was returned. When she came back to her body—and she felt sure she had left it—her eyes were stretched wide open, and they were dry, because she found herself staring directly into the sun.

Her father said the Indians had constructed the coil in the Serpent’s tail in order to give the living a sensation similar to that of dying: The body seemed to drop away, and only the spirit lived, set free in the world. But she was not convinced. It seemed to her that it was a way the living sought to expand the consciousness of being alive, there where the ground about them was filled with the dead. It was a possibility they discussed, alone in the fields. Their secret: that they both shared the peculiar madness of her great-grandmother. It sent them brooding at times over the meaning of this. At other times they rejoiced over so tangible a connection to the past.

Later in her travels she would go to Mexico to a mountain that contained at its point only the remains of an ancient altar, the origin of which no one was certain. She would walk up a steep stair made of stones to the pinnacle of the altar and her face would disappear into the clouds, just as the faces of ancient priests had seemed to disappear into the heavens to the praying followers who knelt in reverence down below. There would again be a rushing out from her all that was surrounding, all that she might have touched, and again she would become a speck in the grand movement of time. When she stepped upon the earth again it would be to feel the bottoms of her feet curl over the grass, as if her feet were those of a leopard or a bear, with curving claws and bare rough pads made sensitive by long use.

In the Capital’s museum of Indians she peered through plate glass at the bones of a warrior, shamelessly displayed, dug up in a crouched position and left that way, his front teeth missing, his arrows and clay pipes around him. At such sights she experienced nausea at being alive.

When blacks were finally allowed into Sacred Serpent Park, long after her father’s crops had been trampled into dust, she returned one afternoon and tried in vain to relive her earlier ecstasy and exaltation. But there were people shouting and laughing as they slid down the sides of the great Serpent’s coil. Others stood glumly by, attempting to study the meaning of what had already and forever been lost.

English Walnuts

“WHY ARE YOU always so sourfaced about it?” some boy would breathe into her bosom in the back seat of his car during the fifties. “Can’t you smile some? I mean, is it gon’ kill you?”

Her answer was a shrug.

Later on she would frown even more when she realized that her mother, father, aunts, friends, passers-by—not to mention her laughing sister—had told her nothing about what to expect from men, from sex. Her mother never even used the word, and her lack of information on the subject of sex was accompanied by a seeming lack of concern about her daughter’s morals. Having told her absolutely nothing, she had expected her to do nothing. When Meridian left the house in the evening with her “boyfriend”—her current eager, hot-breathing lover, who always drove straight to the nearest lovers’ lane or its equivalent, which in her case was the clump of bushes behind the city dump—her mother only cautioned her to “be sweet.” She did not realize this was a euphemism for “Keep your panties up and your dress down,” an expression she had heard and been puzzled by.

And so, while not enjoying it at all, she had had sex as often as her lover wanted it, sometimes every single night. And, since she had been told by someone that one’s hips become broader after sex, she looked carefully in her mirror each morning before she caught the bus to school. Her pregnancy came as a total shock.

They lived, she and the latest lover, in a small house not a mile from the school. He married her, as he had always promised he would “if things went wrong.” She had listened to this promise for almost two years (while he milked the end of his Trojans for signs of moisture). It had meant nothing because she could not conceive of anything going more wrong than the wrong she was already in. She could not understand why she was doing something with such frequency that she did not enjoy.

His name was Eddie. She di

d not like the name and didn’t know why. It seemed the name of a person who would never amount to much, though “Edward” would have suited her no better.

As her lover, Eddie had had certain lovable characteristics—some of which he retained. He was good-looking and of the high school hero type. He was tall, with broad shoulders, and even though his skin was dark brown (and delicious that way) there was something of the prevailing white cheerleader’s delight about him; there was a square regularity about his features, a pugness to his nose. He was, of course, good at sports and excelled in basketball. And she had loved to watch him make baskets from the center of the gymnasium floor. When he scored he smiled across at her, and the envy of the other girls kept her attentive in her seat.

His hair was straight up, like a brush—neither kinky nor curly. A black version of the then popular crew cut. He wore brown loafers, too, with money in them. And turtlenecks—when they were popular—and the most gorgeous light-blue jeans. Which, she was to learn, required washing and starching and ironing every week, as his mother had done, for dirty jeans were not yet the fashion. His eyes were nice—black and warm; his teeth, perfect. She loved the way his breath remained sweet—like a cow’s, she told him, smiling fondly.

Being with him did a number of things for her. Mainly, it saved her from the strain of responding to other boys or even noting the whole category of Men. This was worth a great deal, because she was afraid of men—and was always afraid until she was taken under the wing of whoever wandered across her defenses to become—in a remarkably quick time—her lover. This, then, was probably what sex meant to her; not pleasure, but a sanctuary in which her mind was freed of any consideration for all the other males in the universe who might want anything of her. It was resting from pursuit.

Once in her “sanctuary” she could, as it were, look out at the male world with something approaching equanimity, even charity; even friendship. For she could make male friends only when she was sexually involved with a lover who was always near—if only in the way the new male friends thought of her as “So-an-so’s Girl.”

In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: Prose

In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: Prose In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women: Stories of Black Women

In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women: Stories of Black Women Anything We Love Can Be Saved

Anything We Love Can Be Saved The Color Purple

The Color Purple By the Light of My Father's Smile

By the Light of My Father's Smile The Third Life of Grange Copeland

The Third Life of Grange Copeland You Can't Keep a Good Woman Down

You Can't Keep a Good Woman Down The Temple of My Familiar

The Temple of My Familiar Possessing the Secret of Joy

Possessing the Secret of Joy We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For

We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For The Way Forward Is With a Broken Heart

The Way Forward Is With a Broken Heart Meridian

Meridian Revolutionary Petunias

Revolutionary Petunias A Poem Traveled Down My Arm

A Poem Traveled Down My Arm Once

Once Horses Make a Landscape Look More Beautiful

Horses Make a Landscape Look More Beautiful Living by the Word

Living by the Word In Love and Trouble

In Love and Trouble The Color Purple Collection

The Color Purple Collection Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart

Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart Color Purple Collection

Color Purple Collection Taking the Arrow Out of the Heart

Taking the Arrow Out of the Heart The World Will Follow Joy

The World Will Follow Joy Meridian (1976)

Meridian (1976) Absolute Trust in the Goodness of the Earth

Absolute Trust in the Goodness of the Earth In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens

In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens